I find myself even more confused today then I ever have been with my paintings. Talking to people has made me feel more alienated in my frustrations. And I feel better realizing the history that has gathered behind me...

I find myself even more confused today then I ever have been with my paintings. Talking to people has made me feel more alienated in my frustrations. And I feel better realizing the history that has gathered behind me...There is something deceivingly simple about the idea of the still life, something I have (until this point) refused to think about. Still lifes are not at all simple, they hold a history of symbolism and meaning, not only from the objects in them, but in the way they are painted. I find myself amused by the idea that when looking at a still life, you are looking at a captured moment of fresh fruit, as seen through the painter's eyes. Something about painting feels fresh, like it was just painted yesterday. This feeling is especially evident in the still life paintings of Chardin. These paintings are almost real-er then real.

Maintaining a stage-like space similar to Chardin but completely different handling of paint is Morandi.

I recently saw a Morandi still life at the Princeton Art Museum (by the way, an amazing collection that is obviously well-funded). The idea of painting only this banal genre scene and only these vases for his whole life is mind-boggling. The texture of his paintings is alluring, whereas they feel dry and wet at the same time. The brushwork feels effortless. Also in the museum were paintings by Cezanne and Soutine, two artists that have explored the idea of 'natura morta' and took it even more literally.

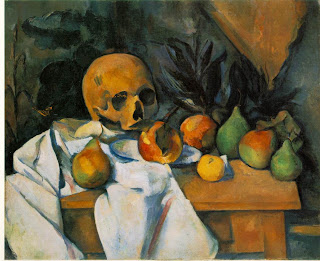

I recently saw a Morandi still life at the Princeton Art Museum (by the way, an amazing collection that is obviously well-funded). The idea of painting only this banal genre scene and only these vases for his whole life is mind-boggling. The texture of his paintings is alluring, whereas they feel dry and wet at the same time. The brushwork feels effortless. Also in the museum were paintings by Cezanne and Soutine, two artists that have explored the idea of 'natura morta' and took it even more literally.  Cezanne puts a skull in the painting, referencing death and decay. He places the skull next to fruits, of which are eternally stuck in their bountiful ripeness. It is a visual juxtaposition that describes the imminent yet impossible death of the fruits. The skull is painted in what seems to be the same space and style as the fruits, which further emphasizes the juxtaposed items. Cezanne represents the epitome of the still life painters, and the objects that were chosen for the still life paintings determine the meaning of the painting, and that choice holds great importance.

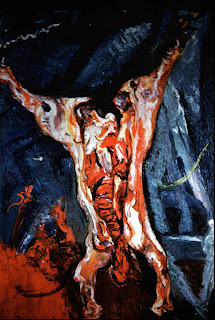

Cezanne puts a skull in the painting, referencing death and decay. He places the skull next to fruits, of which are eternally stuck in their bountiful ripeness. It is a visual juxtaposition that describes the imminent yet impossible death of the fruits. The skull is painted in what seems to be the same space and style as the fruits, which further emphasizes the juxtaposed items. Cezanne represents the epitome of the still life painters, and the objects that were chosen for the still life paintings determine the meaning of the painting, and that choice holds great importance.  Furthermore, Soutine explores the idea of painting a splayed carcass of an animal, posing a question to the viewer: is that inside us too? The idea of painting a dead animal makes literal the idea of the still life. The idea of painting the gushing organs from an opened up carcass partially disgusts me. On the other hand, these paintings are beautifully painted in a shade of red that doesn't make me gag. Seeing a painting like this hanging next to a landscape or a still life makes me think of the acceptance and willingness from the viewer to see something in a museum that could possibly be disgusting or revolting.

Furthermore, Soutine explores the idea of painting a splayed carcass of an animal, posing a question to the viewer: is that inside us too? The idea of painting a dead animal makes literal the idea of the still life. The idea of painting the gushing organs from an opened up carcass partially disgusts me. On the other hand, these paintings are beautifully painted in a shade of red that doesn't make me gag. Seeing a painting like this hanging next to a landscape or a still life makes me think of the acceptance and willingness from the viewer to see something in a museum that could possibly be disgusting or revolting. Hans Holbein paints an aristocratic portrait called "The Ambassadors," while keeping a hidden secret (that is distractingly obvious after revelation) that reveals an anamorphic skull.

This painting has been extremely studied, in fact, I'm sure every into to art history has mentioned it. The only way to view the skull would be either tilt the screen or paper that is in view, or in person to basically get down on the ground and look at the perfect angle. It's a strange painting because it feels like a common portrait with still life items surrounding it, and yet, there's this obsession with the stopping of time and death that becomes obvious upon the realization of the skull. Unfortunately, after that realization, there is no other way to reconcile the image of the skull, hence my brain constantly is trying to put together that image.

This painting has been extremely studied, in fact, I'm sure every into to art history has mentioned it. The only way to view the skull would be either tilt the screen or paper that is in view, or in person to basically get down on the ground and look at the perfect angle. It's a strange painting because it feels like a common portrait with still life items surrounding it, and yet, there's this obsession with the stopping of time and death that becomes obvious upon the realization of the skull. Unfortunately, after that realization, there is no other way to reconcile the image of the skull, hence my brain constantly is trying to put together that image. This leaves me feeling somewhat comforted after linking together only several of the infinite artists that inspire me on a day to day basis, while solidifying even more the idea that I do not want to paint really-real paintings of fruits or vases, not even potraits. Although it has worked for this artist, there are limitations to how much a viewer can take out of paintings like say, Holbein's "Ambassadors".

No comments:

Post a Comment